Walk the walk of old Japan in Saitama

features

Updated on:2024.11.12

The Edo period saw societal unification on a scale that had never been seen before in Japan. One thing which contributed to this was the rapid development of pedestrian highways between major checkpoints in Japan; namely, the old capitol Kyoto, and the new one Edo. The ruling “shogunate” government required all regional lords to make regular trips into the capitol of Edo Tokyo, and this constant flow of entourages from all over Japan made these pedestrian highways a highly developed string of “post towns” for the travelers, with accommodation, “tea-shops” for tea, alcohol, and food, as well as general stores with supplies they might need to continue on after a one or two night stay.

Being just north of the original starting point of Nihonbashi in Tokyo, Saitama has two of these highways running through: the Nakasendo, which is the mountainous route leading to Kyoto, and the Nikko-Kaido, which is the route leading to Toshogu, the mausoleum of the Tokugawa family shogunate rulers. The original walking routes set the stage for road and rail development, and many of the post towns are major stations to this day.

Nakasendo

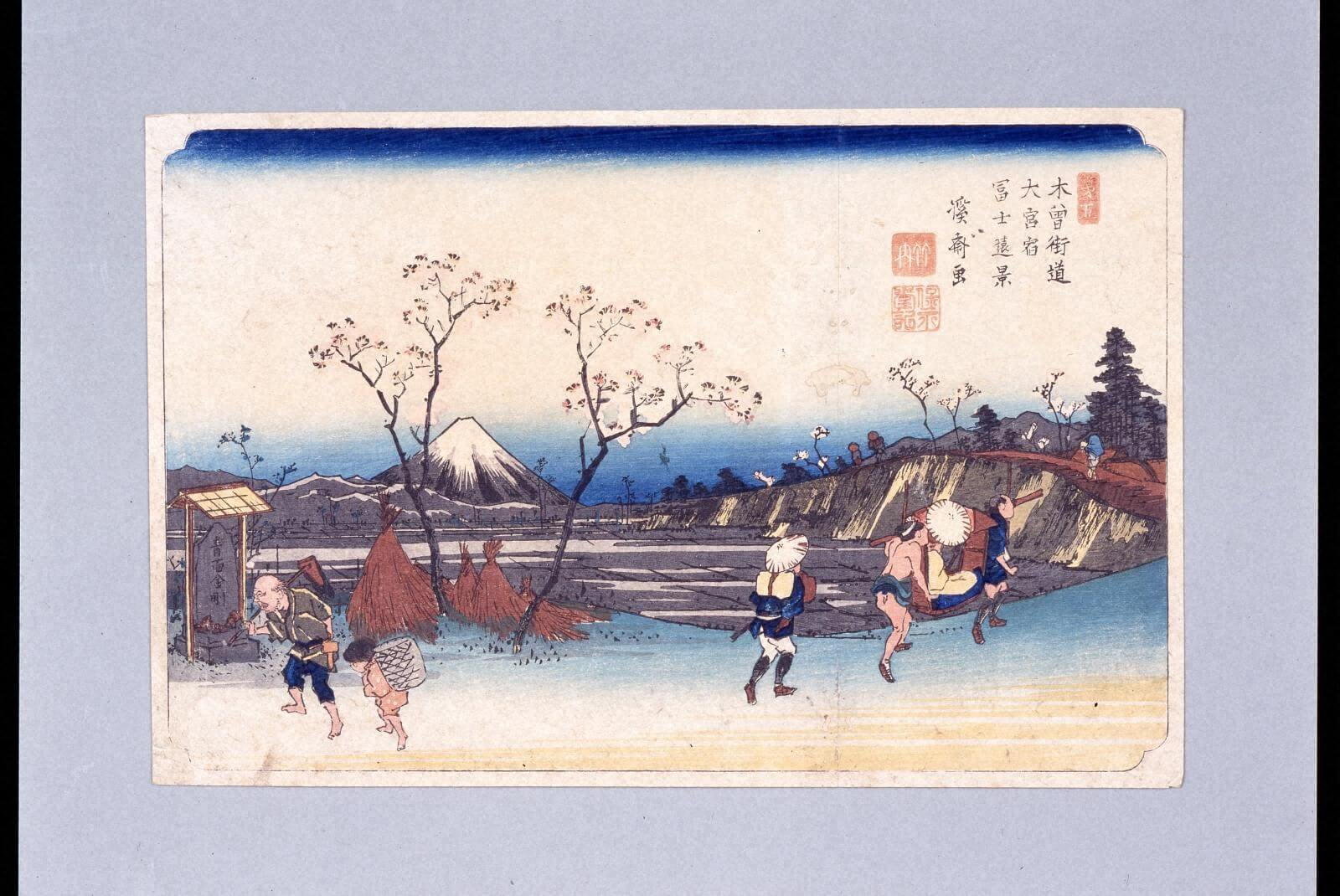

The Nakasendo, along with the Tokaido, were the two routes to Kyoto, the former going going up through Saitama, and eventually cutting west to Kyoto, and the latter along the southern coast through Odawara and below Mt. Fuji. The Nakasendo was said to be an easier journey, with less rivers to cross, with a total distance of 534 kilometers.

The total number of post towns on the Nakasendo was 69, and the first four stops are stations you may already know from a visit to Tokyo or Saitama: Itabashi, Warabi, Urawa, and Omiya. While roads and development have glossed over the original Nakasendo, modern day highway 17 that heads north through Saitama is largely faithful to the original direction of the Nakasendo, and could make for a good trek if you want to simulate a portion of the walking adventure.

“Omiya-shuku”, as it was called during the Edo period, was among the largest post towns in the early part of the trip, and established itself as a major checkpoint in the journey. This is the reason that even today, many of the commuter and bullet train lines pass through Omiya before heading to different parts of Japan. It is very much like a second Tokyo in that sense.

Omiya-shuku was an important connection point between Urawa-shuku to the south, and Ageo-shuku to the north, but another reason for its growth during this period was the presence of Hikawa Shrine. The Nakasendo route was directly connected to the path leading to the shrine, and just before the “Torii” gate into the main shrine area, the Nakasendo branched off to the west to continue on. If you walk along the path to Hikawa Shrine (about 1km), you’ll be walking a portion of the road the noble entourages used going to and from Edo!

Nikko Kaido

The other major highway leading through Saitama is the Nikko Kaido, and this one goes a bit off to the east of where the Nakasendo stretches. The distance from Tokyo to Nikko is shorter than the Nakasendo, with only 21 stations compared to 69 on the Nakasendo.

The importance of the Nikko Kaido lies with the endpoint of Toshogu shrine in Nikko, where the generations of the Tokugawa shogun leaders are enshrined. Toshogu was first established by Tokugawa Hidetaka, who enshrined his father Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first shogun leader of the Edo period. The development of the highway came from regular pilgrimages of both shogunate entourages and other travelers to the shrine.

The first three major stops on the Nikko Kaido are again stations many will know from a visit to Saitama: Soka, Koshigaya, and Kasukabe.

One notable traveler who detailed his journey in his memoirs was a poet by the name of Matsuo Basho. A part of the dirt and cobblestone path he walked is preserved in Soka, beautifully lined with pine trees. He romanticized the idea of walking as a crucial part of any journey, and has since inspired a culture of walking and exploration for generations upon generations.

Much of Japan remains untouched from long ago. While appearances have changed through industrialization and modernization, Japan has done a good job of leaving gems here and there that whisk you back to old times. The Nakasendo and Nikko Kaido are living legacies showing how Japan was originally connected on foot, and also encourage you to rely on your feet while uncovering the wonders of old and new Japan. While the train system of Japan is unparalleled, we highly recommend taking the time to travel by foot between stations along the routes mentioned here or others, and you’ll truly see how remarkably interconnected Japan is on foot.